Introduction

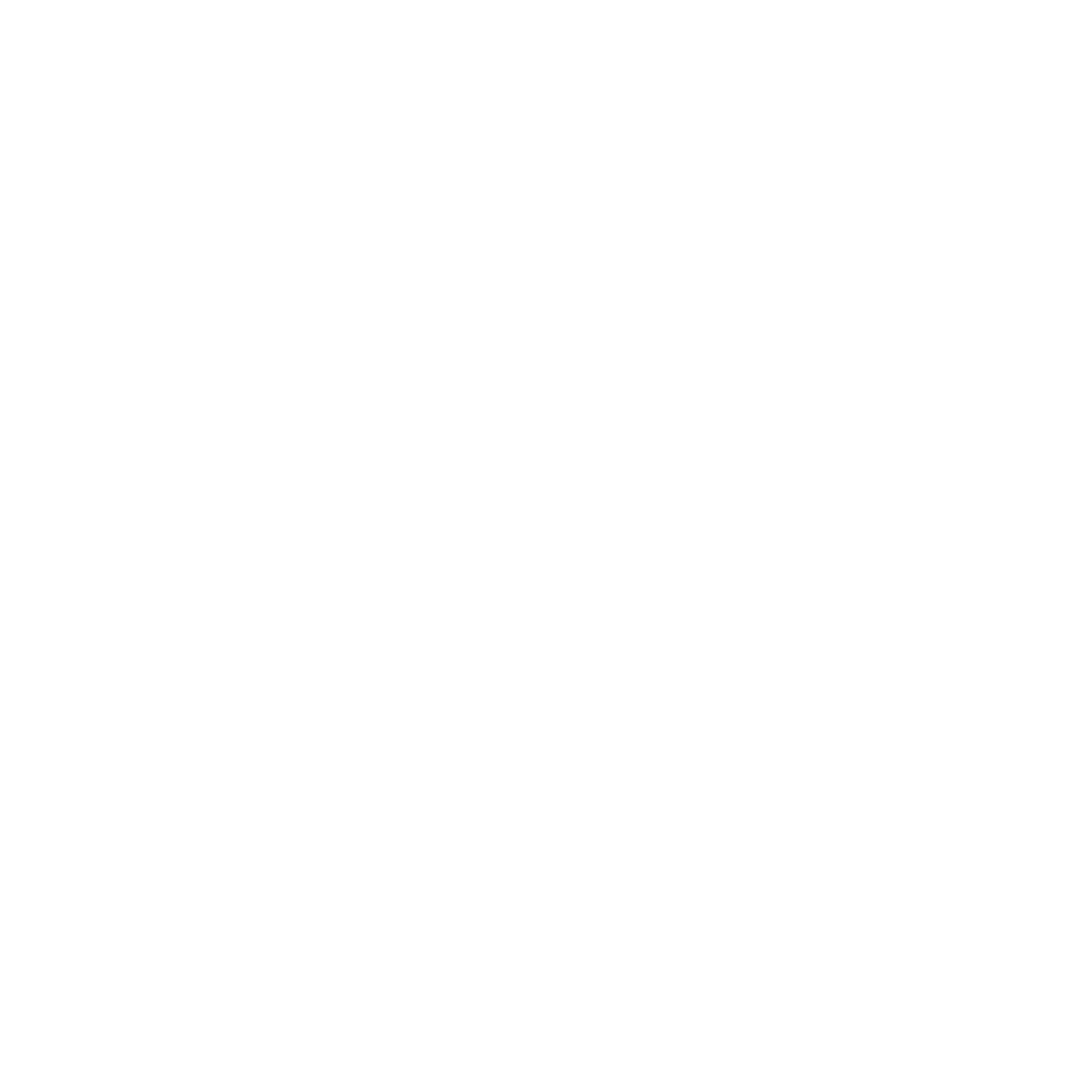

Let's assume we are working on a text classification task where the input to the model is a word, and we want to classify that as either a person or a country. The input word here is Dhoni, an Indian cricket team captain. We would type the word Dhoni As a person. If the input is Australia, we would like to classify it as a country, not a person.Now think about how this model will process input words; if it has seen Dhoni before, it can classify them as a person. But let's say the input word is Cummins, the suffix of a cricketer named Pat Cummins. So how this model will classify this word as a person is challenging. We might be a little confused about how the model would do it. The essence here is how we can capture the similarity between two words. The similarity in terms that Cummins is a person and cricket player simultaneously, and the word Australia and Cummins are not very similar.

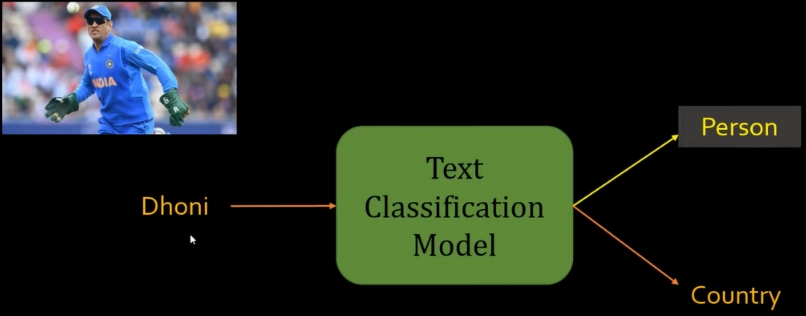

Let's think about if we have two homes, how do we say they are similar. We will get the features of this home. The parts are bedroom areas and bathrooms. So based on the characteristics of these homes, we can say they are similar. But when we have a third home which is a bigger one, we can say the second home and third home are not identical. If we can derive the features for an object, then by comparing those features, we can tell if those two objects are similar. Similarly, consider translating these words Dhoni Australia, etc., into features. If we can create the vectors of all the features and compare these two vectors, then we can say that Dhoni is more similar to Cummins, and Cummins and Australia are not identical.

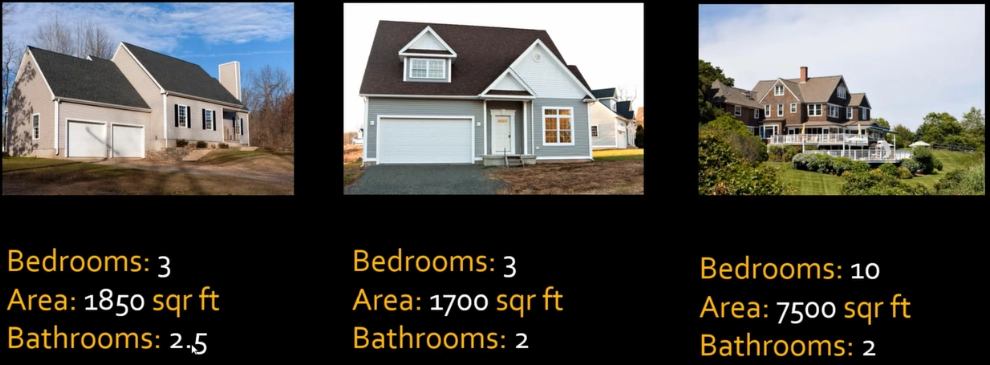

If we build a model on cricket vocabulary, we might have some terms like Ashes Australia, Bat, etc., and we can generate feature vectors of these words. These vectors are called word embedding. But the essence is that when we compare feature vectors, the word embedding of Cummins and Dhoni will find that these two are similar, whereas Australia and Zimbabwe are similar, so these two are countries. This is a compelling concept, and one of the ways we can generate the word embedding from the word is by using word2vec. But, the issue with word2vec is that it cannot differentiate the meaning of a particular word in different contexts.

For example, the fixed embedding of the word 'fair' is incorrect because the definition of fair in both sentences is different. We need a model which can generate a contextualized meaning of a word. This means we can look at the whole sentence, and based on that; we can create the number representation for a word.

BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) allows us to do the same thing. It will generate contextualized embedding meaning when we have these two sentences. The word embedding of the world fair is different, and at the same time, it will capture the essence of a word in the right way. BERT can also generate embeddings for entire sentences.

Architecture of BIRT

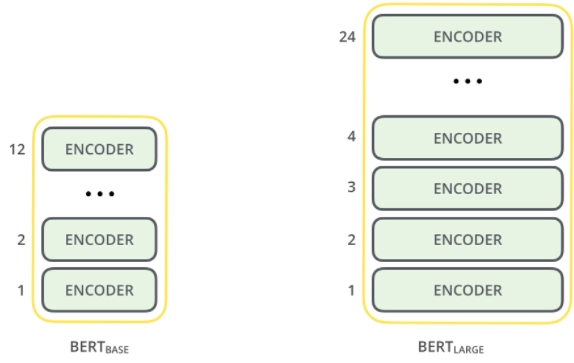

There are two model architectures of BIRT.

BASE BIRT- Comparable in size to the open AI transformer to compare performance.

BERT LARGE- Ridiculously huge model which achieved the state-of-the-art result.

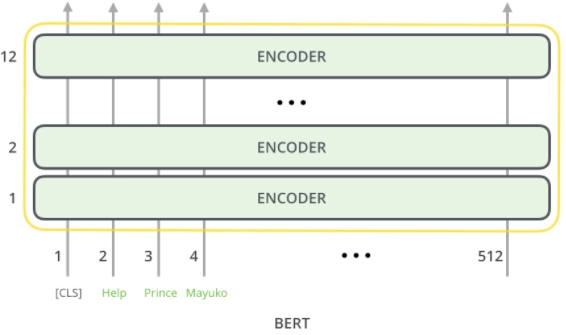

BERT models have many encoder layers, 12 for the base version 24 for the large version. These also have more extensive feed-forward networks. The first input token is supplied with a unique classification token that will become apparent later on. The Vanilla encoder of the Transformer BIRT takes a sequence of words as an input that keeps flowing up the stack. Each layer applies self-attention and passes its result through a feed-forward Network, and then it hands it off to the next encoder. Each position outputs a vector of hidden size. We focus on the output of only the first position for the sentence classification. The vector can now be used as an input for a classifier of our choosing.