Introduction

A web service is a collection of web-based elements that facilitates data transfer between applications or systems and incorporates open protocols and standards. It can be used, published, and located online. There are many different kinds of web services, including RWS (RESTful Web Service), WSDL, SOAP, and many more. In this article, we discussed REST — Representational State Transfer, REST Interface through CherryPy, and also discussed tools through which CherryPy's architecture is implemented.

REST — Representational State Transfer

A kind of remote access protocol that sends the state from the client to the server, allowing the state to be changed without having to call external programs.

- Does not specify any particular structure, encoding, or methods for generating helpful error messages.

- Performs state transfer activities via HTTP "verbs."

- Utilising URLs, the resources are each uniquely recognized.

- It is an API transport layer rather than an API.

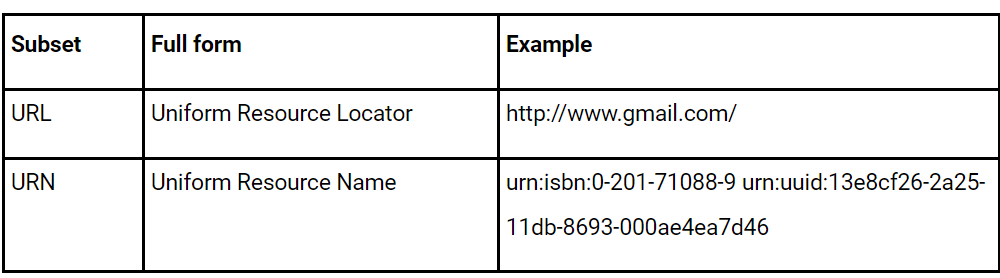

REST provides a single way to carry out operations on these resources while maintaining the nomenclature of network resources. At least one identifier is used to identify each resource. If HTTP is used as the foundation for the REST infrastructure, then these identifiers are known as Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs).

Nowadays, it's common for web apps to expose some type of data model or computing capabilities. Without going into specifics, one tactic is to adhere to Roy T. Fielding's REST principles.

The URI set's subsets are followed in some cases.

Let's walk through a brief example of a very simple web API that only loosely adheres to REST concepts.

import random

import string

import cherrypy

@cherrypy.expose

class StringGeneratorWebService(object):

@cherrypy.tools.accept(media='text/plain')

def GET(self):

return cherrypy.session['mystring']

def POST(self, length=8):

some_string = ''.join(random.sample(string.hexdigits, int(length)))

cherrypy.session['mystring'] = some_string

return some_string

def PUT(self, another_string):

cherrypy.session['mystring'] = another_string

def DELETE(self):

cherrypy.session.pop('mystring', None)

if __name__ == '__main__':

conf = {

'/': {

'request.dispatch': cherrypy.dispatch.MethodDispatcher(),

'tools.sessions.on': True,

'tools.response_headers.on': True,

'tools.response_headers.headers': [('Content-Type', 'text/plain')],

}

}

cherrypy.quickstart(StringGeneratorWebService(), '/', conf)Save this as tut07.py and execute it as follows:

$ python tut07.pyLet's go over a couple of things in detail before we see it in action. Up until this point, CherryPy had been matching URLs by building a tree of exposed methods. We wish to emphasize the significance of the HTTP methods used in the actual requests in the context of our web API. In order to make them all instantly visible, we defined methods with their names and decorated the class itself using cherrypy.expose.

The default mechanism of matching URLs must then be replaced with a method that is aware of the entire HTTP method shenanigans. This is what goes in line 27 when we make an instance of the method dispatcher.

Finally, we ensure that GET requests will only be fulfilled for clients who accept that content type by forcing the responses' content type to be text/plain and setting an Accept: text/plain header in the request. However, we only do this for that particular HTTP method since it wouldn't signify much for the others.

We won't be utilizing your browser for the duration of this tutorial because we need to use a Python client to properly test our web API.

Please execute the following command to install requests:

$ pip install requestsThen fire up a Python terminal and try the following commands:

>>> import requests

>>> s = requests.Session()

>>> r = s.get('http://127.0.0.1:8080/')

>>> r.status_code

500

>>> r = s.post('http://127.0.0.1:8080/')

>>> r.status_code, r.text

(200, u'04A92138')

>>> r = s.get('http://127.0.0.1:8080/')

>>> r.status_code, r.text

(200, u'04A92138')

>>> r = s.get('http://127.0.0.1:8080/', headers={'Accept': 'application/json'})

>>> r.status_code

406

>>> r = s.put('http://127.0.0.1:8080/', params={'another_string': 'hello'})

>>> r = s.get('http://127.0.0.1:8080/')

>>> r.status_code, r.text

(200, u'hello')

>>> r = s.delete('http://127.0.0.1:8080/')

>>> r = s.get('http://127.0.0.1:8080/')

>>> r.status_code

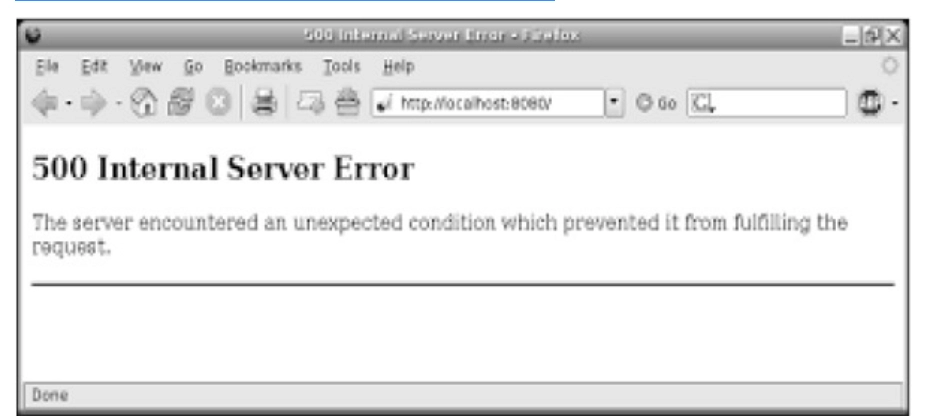

500The reasons for the first and final 500 responses are because, in the former, it doesn't exist after we've erased it, and in the former, we haven't yet formed a string through POST.

You can see how the application responded in lines 12–14 when our client asked for the created string in JSON format. The web API returns the proper HTTP error code because it is set to only support plain text.